O.k., by now we all know that cookies and spyware track our every move on the internet, hoping to figure out our likes and dislikes to show us ads for things we might want to buy. And more and more, these are cross-referenced over many websites, so one gets advertising that has nothing to do with one's activity on a particular site. Buy a gag gift, or a serious gift for someone with opposite tastes, and you're mislabeled for months. And even accurate labeling can be contrary to those buying impulses we actually respond to when we're on a spending spree.

One thing this model doesn't take into account is the fact that the web is now used for everything. Wait a minute -- isn't that good for these advertisers? Maybe not. The fact that the web must be used undercuts its predictability for the user's true tastes. In the early days, the web was an adventure, a playground. Now many people spend most of their online time doing necessary things they don't want to do -- the busy housewife doing online business chores, the student doing homework.

But it's still also a playground -- an escape from those business chores, etc. -- and yes, an escape from the very core of one's identity. While playing an online asteroid-shooting game, I want to be able to fantasize that I'm an astronaut on a dangerous mission, not be constantly reminded that I'm a middle-aged housewife in the midwest. And while this cross-webpage advertising is annoying to me, it's downright cruel to people who have been searching online for help with serious health problems. Imagine not being able to spend an hour, or even a few minutes, relaxing without a reminder of your illness always in some corner of the screen.

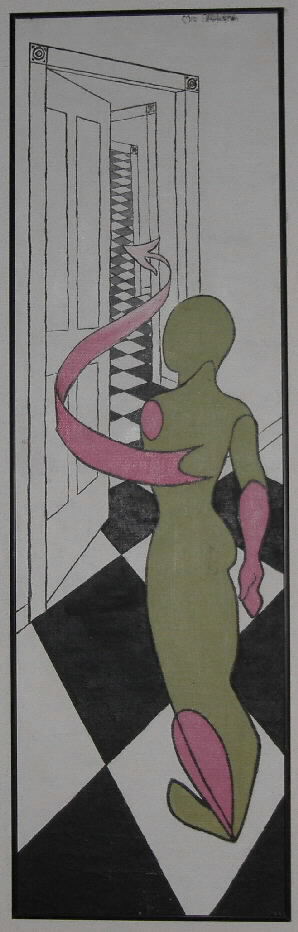

For the things we need, we probably already have sources. Or, if we don't, we'll search for them. It's mostly the fun stuff, the luxuries, we don't know we "need." And the things we get for fun, for luxury, for show, tend to correspond to our imagined selves more than our "real" selves. Basing advertising on our physical limitations, or the limitations other see in us -- even if these identifiers can be kept accurate -- doesn't make sense.

We should have some control over what ads -- or at least what general types of ads -- are shown to us, perhaps even situationally. An impotent man, for instance, could forbid impotence products from being shown when he's playing online shooting games and wants to feel macho. A person who has just lost a loved one could completely forbid any ads about funeral, cemeteries, or any other-death-related products and services. (Again, merely an annoyance when the deceased was old and sick and had lived a full life, but horribly cruel for parents who has lost a young child to have in their face all of their online time.)